The Audition Trap: Why Panel Interviews Create False Negatives in Hiring

Fair To Who: How Panel Interviews Miss The People You Need Most (Field note context)

Field note context

When I say ‘best operators,’ I mean people whose value shows up once they are inside complex, stakeholder-heavy systems, not people who are necessarily the best talkers in a one-way audition. Panels are quite good at finding strong performers for roles that truly are about performance in the room. They are weaker at detecting the people who quietly hold the system together once the cameras are off.

This piece sits next to a few other stories about what systems really do to people:

- What the Katrina book was really for looks at how we document response in ways that protect the people who did the work, instead of sanitizing them out of the record.

- Guarding the room looks at how to keep a technical discussion focused on what actually matters for funding decisions.

- Capacity protects. Heroics consume. uses my Hurricane Florence deployment and West Nile / GBS diagnosis to show what happens when we build systems on heroics instead of capacity.

This one takes the same pattern and applies it to hiring and evaluation.

Specifically, to a tool we keep calling “fair.”

Panel interviews.

The room where the job does not happen

Here is the simple version.

In the work I do, I am effective when:

- I am in the room or on virtually with stakeholders

- We can ask each other clarifying questions

- I can check what they really mean

- We can adjust in real time as new information shows up

That is how actual stakeholder management works.

There is always a back and forth.

The panel interview room is the opposite.

I walk in (or log on to Zoom, etc).

They have their questions prepared.

I have no idea what they are.

They ask one.

I get one shot at a monologue answer.

No clarifying questions.

No feedback loop.

They score my performance and move on.

That is not how the job works.

That is how an audition works.

The Feedback Loop Problem

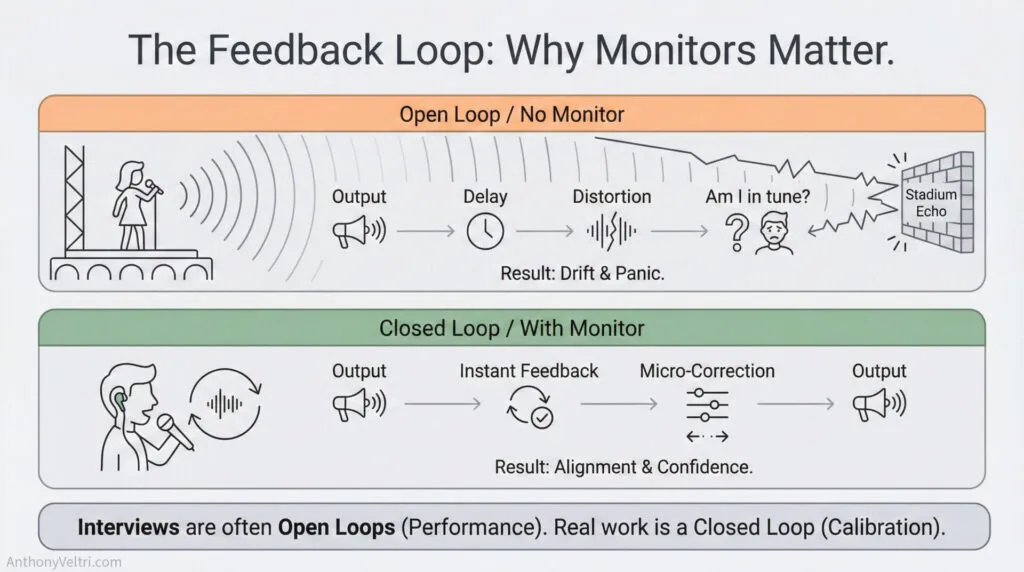

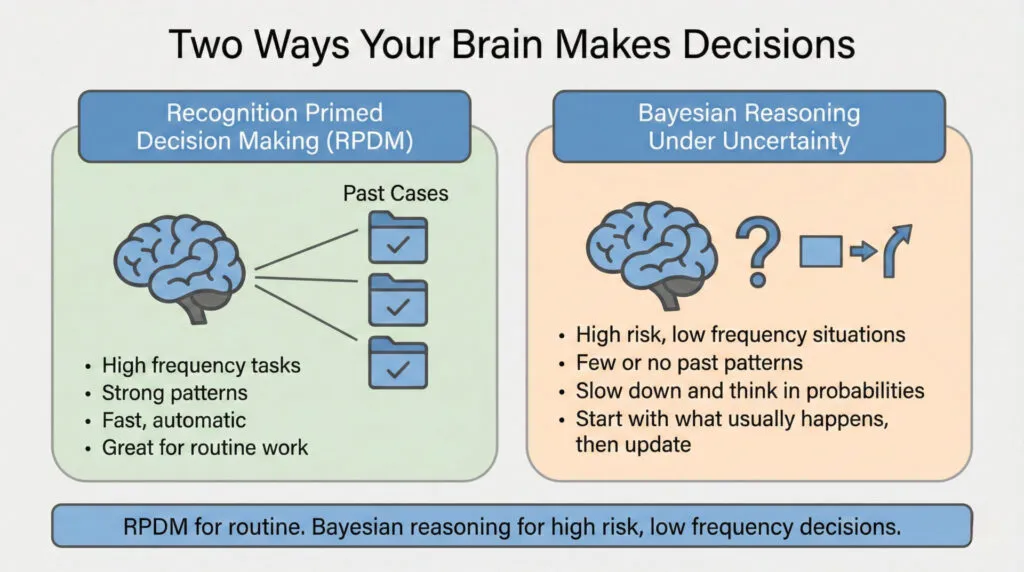

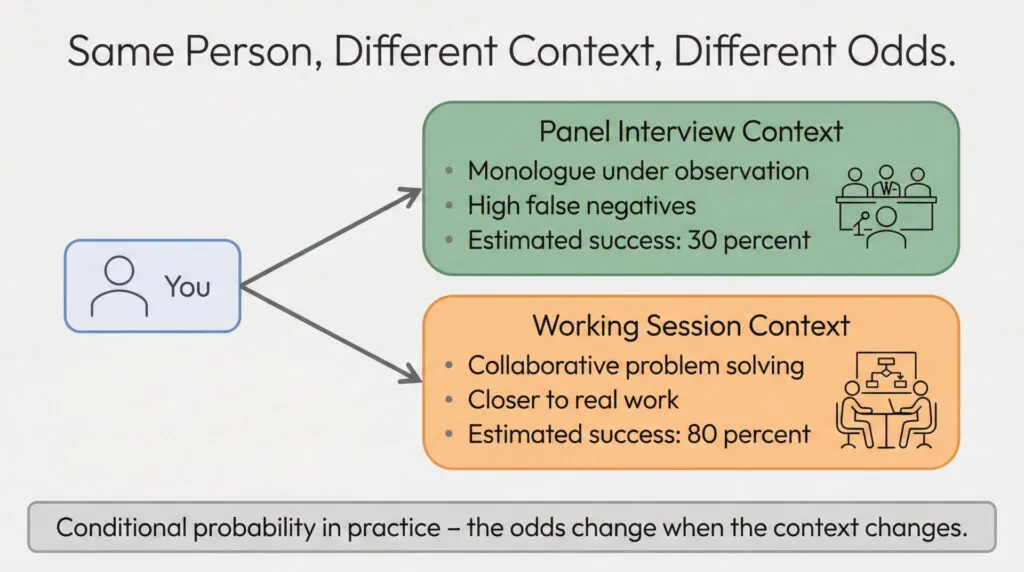

Some operators excel in collaborative environments but struggle in one-way performance formats. This is not just mindset (it is how they are wired). The same traits that make someone effective at reading rooms and building trust (iterative thinking, need for clarification, visible authenticity) can work against them in monologue-style auditions where there’s no feedback loop.

Even professional singers who know the national anthem cold use an earpiece monitor in stadiums. In large spaces, sound bounces back delayed and distorted. Without that monitor, they drift off pitch – not because they don’t know the song, but because the feedback loop is broken.

Panel interviews create the same problem for some operators. You know the material. You have real stories. But with no way to ask “when you say stakeholder management, are you more worried about A or B?” and no signal on whether your first thirty seconds landed or confused them, you’re performing into an echo.

They score your one-way performance. They don’t see what you’re like once you start working on something together.

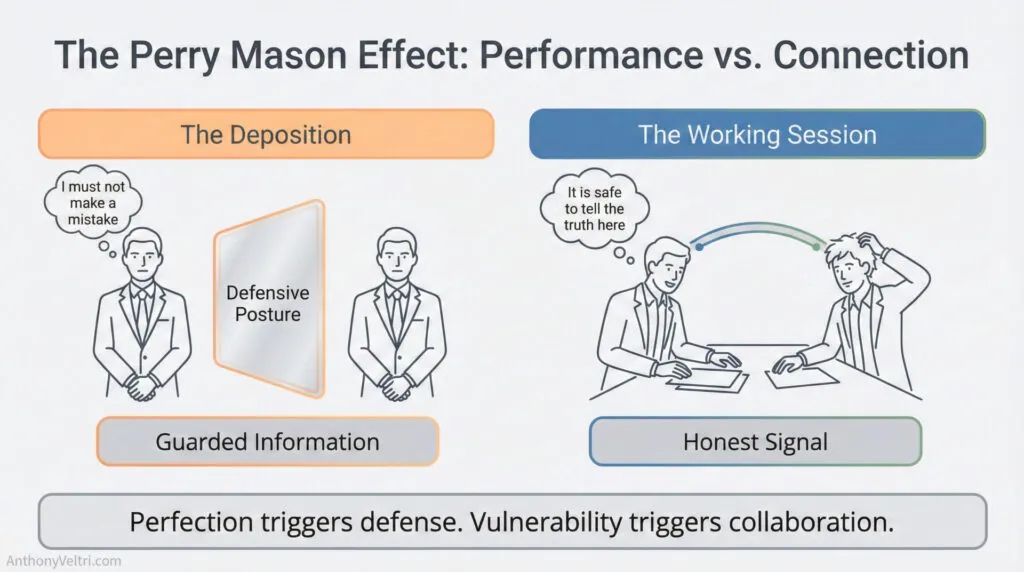

Why my “not okay” makes other people okay

There is a twist here that most interview panels never see.

In real work, one of my advantages is that I show up visibly not perfect.

I am prepared, but I am not performing TV anchor polish.

I can say “I do not know yet. Let us work it out together” without shame.

That has specific effects on stakeholders:

- They stop feeling like they are in a deposition

- They become less defensive

- They answer how things really work, not how they wish things worked

- They trust that I will not weaponize their honesty against them

It is a little like the Perry Mason effect. He looked slightly unkempt and clumsy so people would relax around him. In his case it was intentional.

In my case it is not an act. It is just how my wiring and history present in the room.

The result is the same.

People ease up.

They tell the truth.

We can finally work the real problem.

That skill has almost no way to show up in a scored panel interview.

Feedback enables better interaction and clearer evaluation

What panel interviews actually select for

Organizations use panel interviews in the name of fairness. Everyone gets:

Same questions.

Same time limits.

Multiple assessors.

Score sheets.

On paper, that sounds reasonable.

Look at what the format actually rewards.

Panel interviews tend to select for people who:

- Think and speak quickly in one way formats

- Can improvise polished narratives with minimal feedback

- Enjoy being evaluated in front of a group

- Have practiced the performance piece of leadership more than the listening piece

Those are real skills. They do show up in places like:

- Press conferences

- Board presentations

- Investor roadshows

- Live on camera communication

The key detail is that those settings are not auditions in the same way a hiring panel is.

In a press conference, if someone asks an inappropriate or ambiguous question, you can say, “What do you mean by that” or “No comment.” In a board meeting, the questions are not truly random. You are there as a contributor or subject matter lead, not as a contestant hoping to be chosen.

Even a thesis defense, and I have done two, lives in a different category. It is high-stakes, but the committee expects you to push back, to clarify, to say, “That is outside the scope of this work.” There is room for back and forth and for you to hold your ground as a peer in the conversation.

Panel interviews are different.

You are the supplicant. The panel controls the questions. You are expected to accept each one as legitimate, answer gracefully on the first try, and show perfect composure while they quietly score you.

That is not the same skill as running a board briefing or a live broadcast. It is an audition-style contest.

For roles that actually require stakeholder work, you need something else.

You need people who can:

- Make guarded stakeholders feel safe enough to stop performing

- Ask simple questions that get to the real issue

- Notice when a room tenses up and slow down instead of speeding up

- Operate over multiple conversations instead of one high-stakes audition

Panel interviews barely touch those skills.

In some cases, they invert the signal.

The person who looks a bit less polished in the panel may be exactly the person stakeholders will open up to in the field.

Fair to who

When we say panel interviews are “fair,” we should finish the sentence.

“If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they do not have to worry about the answers.”

Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow

In this context, the wrong question is:

- “Is this interview format fair on paper?”

instead of:

- “Does this format actually measure the capability we are hiring for?”

So:

Fair to who.

Predictive of what.

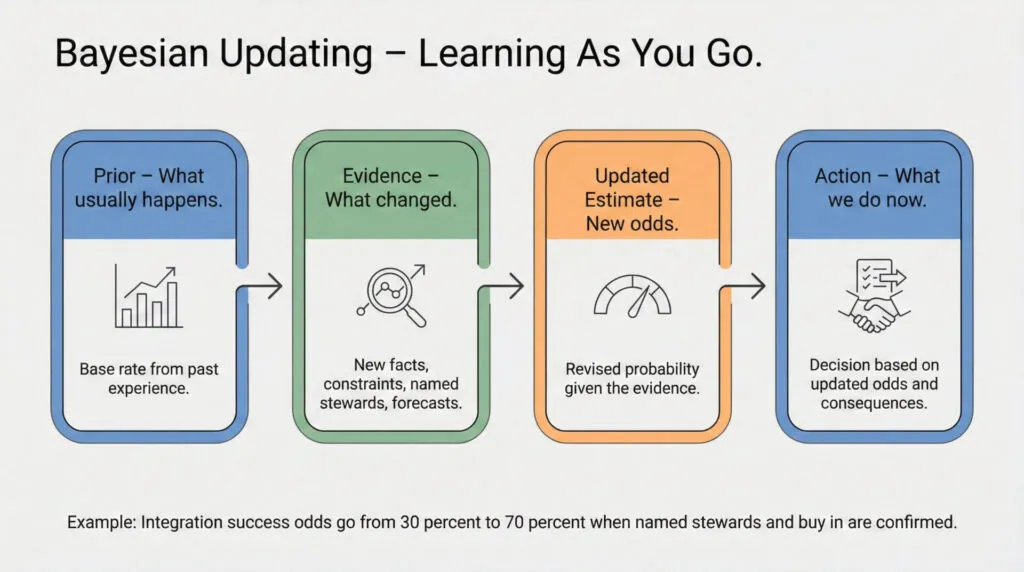

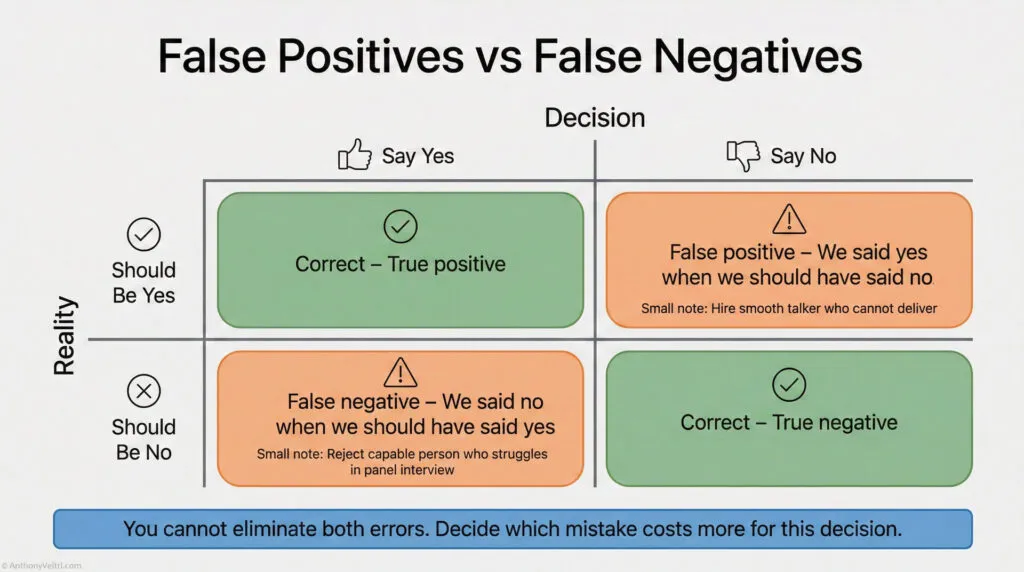

The panel interview optimizes for “Consistency” but generates massive “False Negatives” (rejecting capable people). This matrix highlights the pattern.

Fair to:

- HR processes that need a documented, repeatable format

- Managers who are uncomfortable making judgment calls based on messy human interaction

- Legal teams who want artifacts to point at if someone challenges the decision

Not especially fair to:

- Candidates whose working style makes one-way performance difficult but who excel in collaboration

- People whose strengths show up only after trust is built and the room relaxes

- Operators who have spent twenty years doing the work while others practiced looking good talking about the work

Predictive of:

- How someone handles unknown questions in a staged environment without clarification

- Their tolerance for being judged while they talk

- Their ability to keep a narrative smooth when they cannot check for understanding

Not very predictive of:

- How well they build trust with suspicious stakeholders

- Their ability to co-design a solution in a messy, political environment

- Whether they will quietly hold a system together during year three when the shine has worn off

If you are hiring for performance in the room, panels might be enough.

If you are hiring for work in the world, they are not.

What better signal could look like

You do not have to throw panels away. You do need to surround them with better signal.

Some options that give you more truth and less theater:

1. Conversational interviews

Start with a real problem and talk through it like you would with a peer.

Allow clarifying questions.

Notice how they think and how they listen, not just how they talk.

2. Work samples

Give candidates a short, real scenario ahead of time and have them walk you through their approach.

Let them send a one page brief before the interview so you see how they think in writing.

3. Stakeholder simulations

Instead of a firing squad, simulate a messy meeting.

- One panel member plays a defensive stakeholder

- Another plays someone who is checked out

See how the candidate works the room.

4. Trial projects or probationary contracts

For senior roles, consider a limited statement of work where they actually solve a contained problem with you.

Pay them.

Watch how they engage.

5. Reference conversations about behavior, not adjectives

Ask past colleagues for specific stories of when the candidate navigated conflict, misalignment, or failure.

You are not buying adjectives like “strong communicator.”

You are buying patterns of behavior.

You can still have a panel for consistency and documentation.

Just stop pretending it tells you everything you need.

What this means for leaders

If you lead hiring for roles that live and die by stakeholder work, ask yourself a simple question:

Are we testing for the job, or for our preferred evaluation format.

If your evaluation format:

- Rewards polished monologue

- Punishes people who need a bit of clarification

- Leaves no room for the kind of back and forth your actual stakeholders will expect

Then the format is not fair.

Not to the candidates.

Not to the teams who will live with the hire.

Not to the mission that needs the right person in the role.

You can keep the parts that satisfy HR and legal.

You owe it to your mission to add the parts that satisfy reality.

What this means for people like us

If you read this and recognize yourself, a few practical things:

- Stop treating bad panel performance as a global verdict.

It is one tool, tuned to one kind of performance, in one artificial context. - Go where your strengths can show.

Internal promotions. Referral-based roles. Contract work that leads to hire once people have seen you in action. - Name the format issue without apologizing.

You can say, “I do my best work in collaborative environments, so I may occasionally ask for clarification. I want to make sure I am answering the question you care about.” - Keep records of your real work.

That is what this site is for. Doctrine, case studies, and field notes that show patterns over time.

Part of the reason I write pieces like this is so hiring managers and clients can see how I think before we ever talk. If you recognize your own systems in these patterns, that is the consulting work I now do

Note: This is not license to ignore legitimate feedback or preparation gaps. If multiple panels flag the same concern and it matches what you hear from stakeholders in real work, take it seriously. The point is to separate ‘format mismatch’ from ‘real signal,’ not to dismiss every bad interview as unfair.

Panel interviews are a tool.

They are not a neutral judge.

They are not the work.

If you are designing systems, build evaluation that is fair to the mission, not just fair to the format.

If you are on the other side of the table, remember: the job is what happens after everyone leaves the interview room.

Pedant corner:

Yes, the title is “Fair To Who.”

If you are here for strict grammar, you are probably looking for “whom.”

If you are here for accurate systems thinking, “who” wins.

Pynchon had a line that fits here:

“If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they do not have to worry about the answers.”

If the part of this essay that grabs you is who vs. whom, that is your cue to check what question you are actually asking.

I am a pedant too. I know the textbook answer. I just care more about fixing the system than fixing the case of a pronoun.

Last Updated on December 11, 2025