You are here because work is failing at the seams: handoffs, integrations, shared datasets, cross-team dependencies, “it worked in our system,” and nobody is clearly responsible end to end.

Start here

If you can answer these three questions, you can usually stop the bleeding fast:

- What is the interface? (handoff, API, schema, inbox, spreadsheet, SharePoint list, meeting, approval chain)

- Who owns upstream and who owns downstream? (two owners, not one)

- What is the contract? (what must be true every time this crosses the boundary)

This route is built to get you traction fast: a quick diagnostic, the most common failure mode, and a short path into the relevant Doctrine, Annexes, and Field Notes.

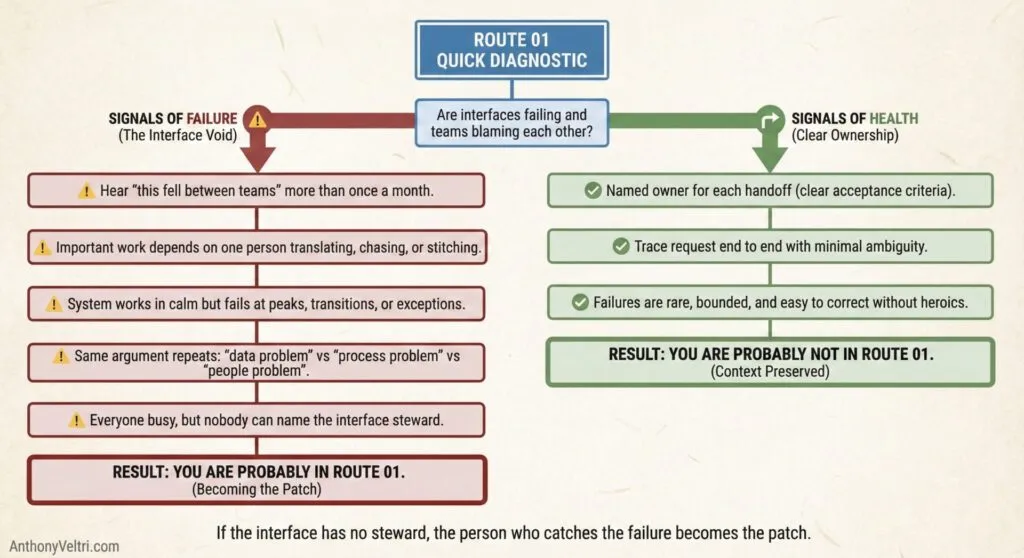

Quick diagnostic

You are probably in this route if:

- You hear “this fell between teams” more than once a month

- Important work depends on one person translating, chasing, or stitching things together

- The system works in calm conditions but fails at peaks, transitions, or exceptions

- The same argument repeats: “data problem” vs “process problem” vs “people problem”

- Everyone is busy, but nobody can name the steward for the interface

You are probably not in this route if:

- There is a named owner for each handoff, with clear acceptance criteria

- You can trace a request end to end with minimal “who owns this” ambiguity

- Failures are rare, bounded, and easy to correct without heroics

What is usually happening

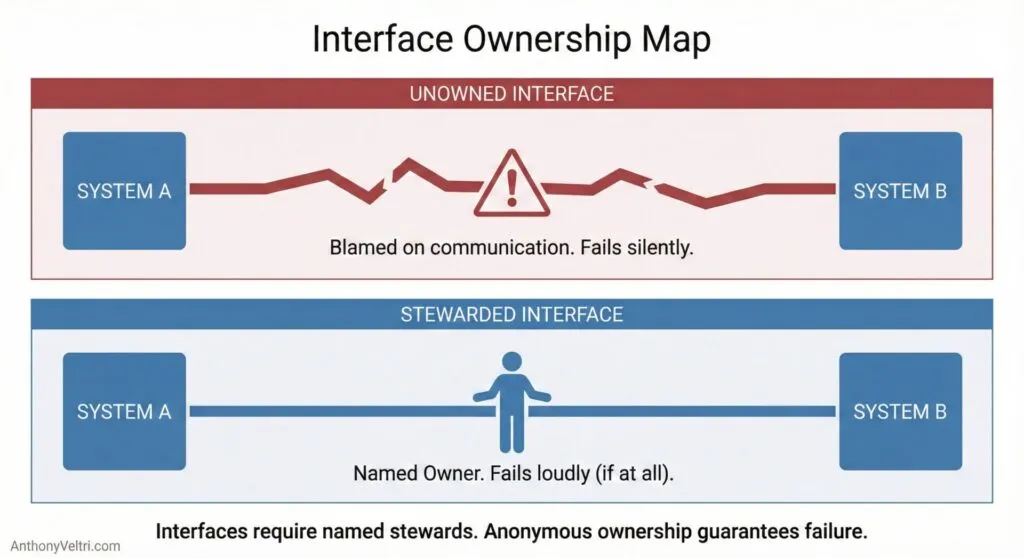

Most organizations do not fail because of one bad tool or one bad person.

They fail because the interfaces are unowned.

When an interface has no steward, the system slowly drifts into one of these patterns:

- Responsibility becomes implied instead of explicit

- Exceptions become normal

- Workarounds become policy

- The “real process” moves into side channels, private docs, and memory

This is why interface problems feel social, but behave like architecture.

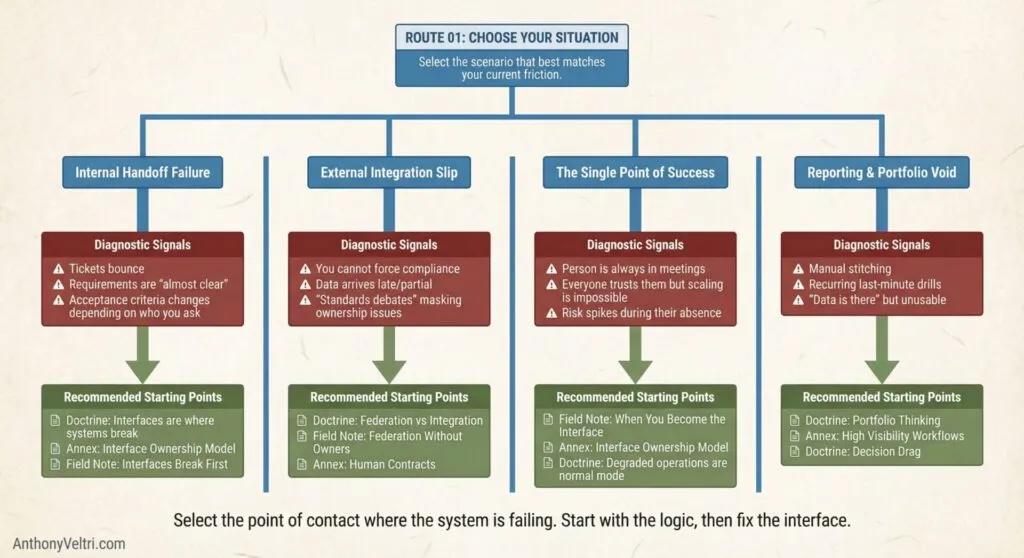

Choose your situation

A handoff keeps breaking between teams

Signals:

- tickets bounce

- requirements are “almost clear”

- acceptance criteria changes depending on who you ask

Start with:

- Doctrine: Interfaces are where systems break

- Annex: Interface Ownership Model

- Field Note: Interfaces Break First

You have a partner, vendor, or multi-agency integration that keeps slipping

Signals:

- you cannot force compliance

- data arrives late, partial, or inconsistent

- disputes show up as “standards debates” but the real issue is ownership

Start with:

- Doctrine: Federation vs Integration

- Field Note: Federation Without Owners

- Annex: Human Contracts

You have a single person who “makes it all work”

Signals:

- that person is always in meetings

- everyone trusts them, but the system cannot scale beyond them

- risk spikes when they are absent

Start with:

- Field Note: When You Become the Interface

- Annex: Interface Ownership Model

- Doctrine: Degraded operations are the normal mode

Your reporting and portfolio rollups feel impossible

Signals:

- manual stitching

- recurring last-minute drills

- “the data is there” but it is not usable

Start with:

- Doctrine: Portfolio thinking

- Annex: High Visibility Workflows

- Doctrine: Decision drag

The recommended path

If you are unsure which situation fits, follow this route:

- Doctrine 03: Interfaces are where systems break

- Annex C: Interface Ownership Model

- Annex A: Human Contracts

- Field Note: Federation Without Owners

- Field Note: When You Become the Interface

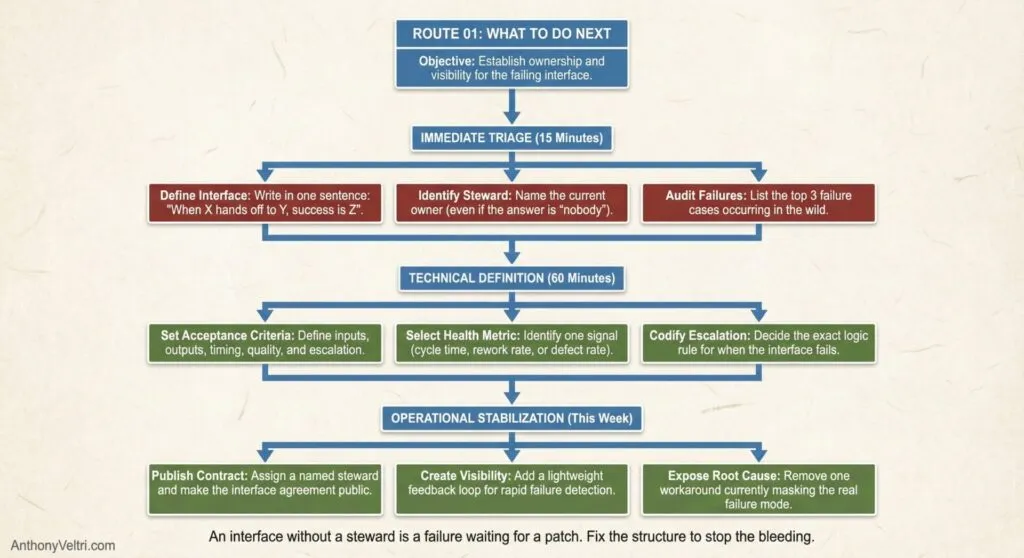

What to do next

In 15 minutes:

- Write the interface in one sentence: “When X hands off to Y, the success condition is Z.”

- Name the current steward, even if the answer is “nobody.”

- List the top 3 failure cases you keep seeing.

In 60 minutes:

- Define acceptance criteria for the handoff (inputs, outputs, timing, quality, escalation).

- Identify one metric that proves the interface is healthy (cycle time, rework rate, defect rate).

- Decide the escalation rule when the interface fails.

This week:

- Assign a named steward for the interface and publish the contract.

- Add a lightweight feedback loop so failures become visible quickly.

- Remove one workaround that is masking the real failure mode.

Why this route works

This is not generic “communication advice.”

Interfaces are load-bearing. When they are unowned, the system forces people to become glue. This route helps you move from invisible glue work to explicit ownership, contracts, and predictable handoffs. When you become the patch, you are transitioning into Stage 3* (The Drill). You have moved past the theoretical safety of ‘The Garden’ and are now exerting agency to prevent a total system failure. This route is designed to help you move from being a ‘temporary patch’ to a permanent ‘steward.’ (* note: click for more information on the stages of competence as they apply here.)

If you want help

Send me 5 sentences (the ground truth of the situation):

- What is the interface (X to Y)?

- What keeps breaking?

- What is at stake if it fails?

- What constraints you cannot change (security, sovereignty, tooling, staffing)?

- What a “good” week looks like

I will help you identify the failure pattern, the top risk, and the next move to restore uptime.