Field Note: Guided Sensemaking Interview

Why external elicitation reveals what self-review cannot

Trying something new (let me know if it works for you). Moving forward, field notes on this site follow a three-part structure: Scene (the experience), Break (the friction or realization), Schema (the extracted pattern and application).

Most of our attention stays fixed on the surface of an event. But as practitioners, we have to see the layer underneath: the professional conditioning and hidden schemas that determine how we respond to friction. Once you learn to find that focal plane, you start seeing the Dragon.

Scene

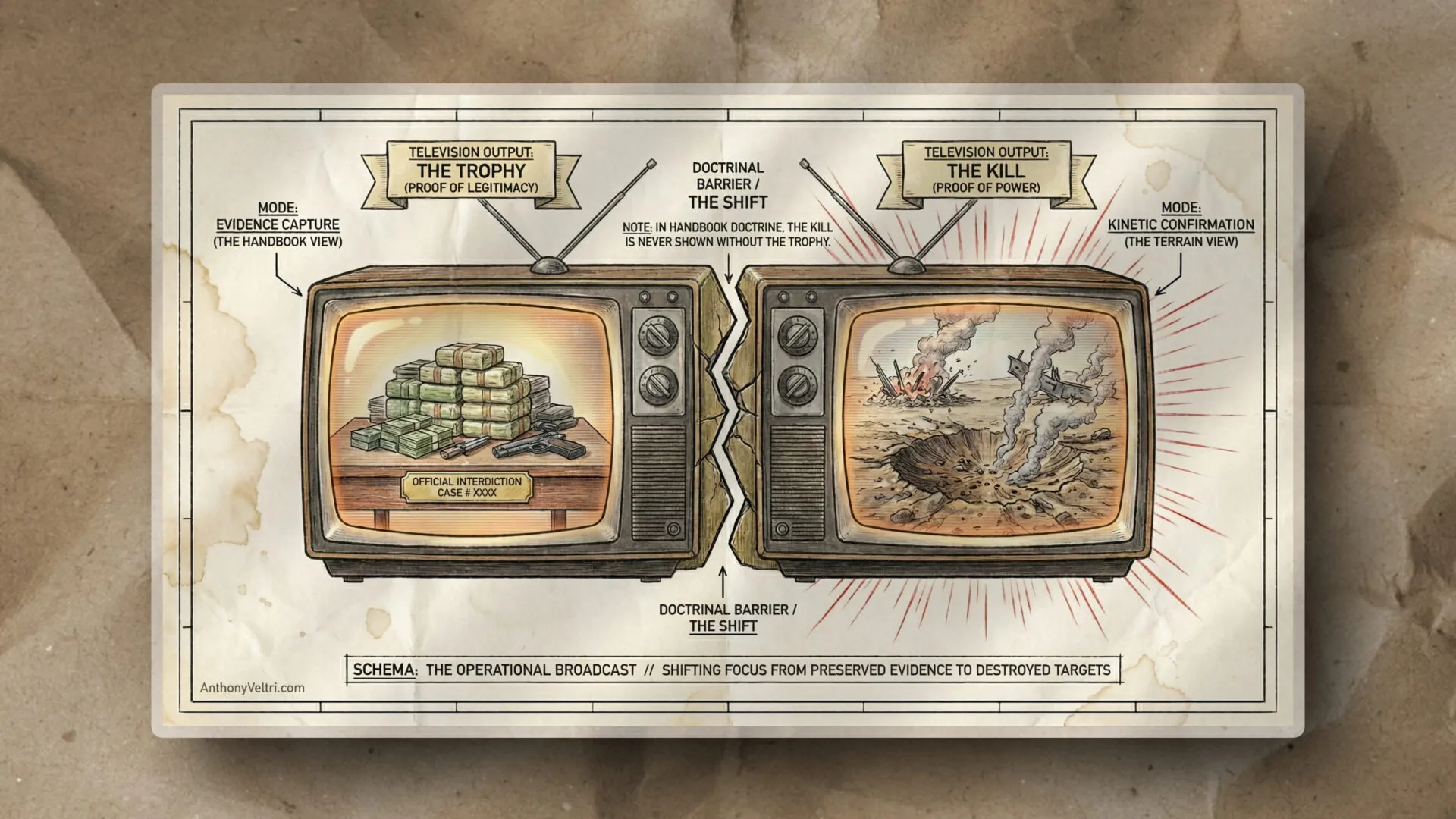

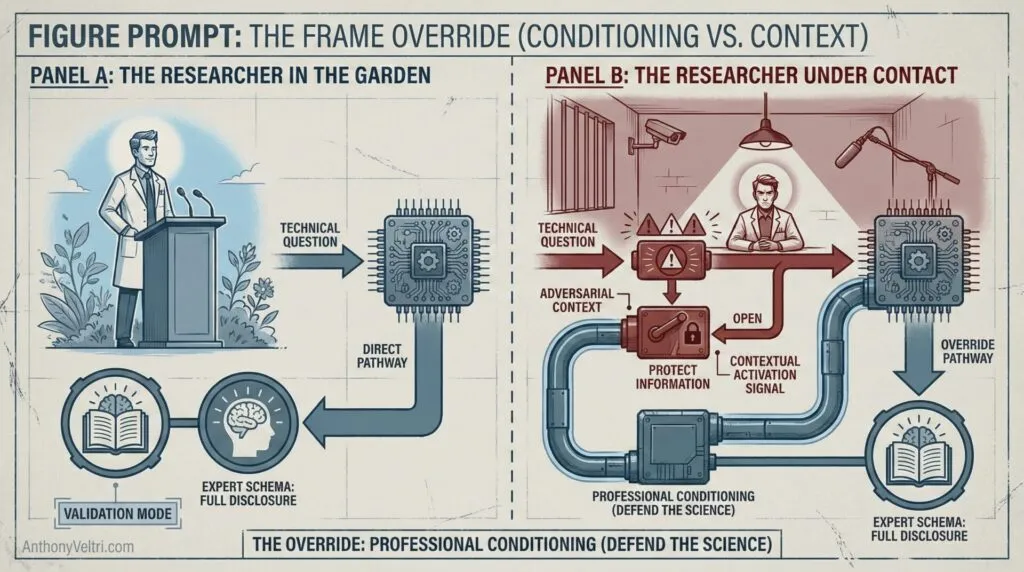

Early months at DHS, receiving anti-elicitation training. The training teaches how adversaries extract sensitive information from willing subjects who don’t realize they’re being targeted. This isn’t interrogation. It’s exploitation of professional conditioning.

The example case: A scientist presents at an international conference overseas. Collegial setting, peer validation, questions that signal genuine interest in their work. The expert schema activates automatically (thesis defense conditioning, conference Q&A training, the entire academic pipeline that rewards providing thorough, detailed justification when questioned about your work). They answer completely because that’s what experts do in that context. They’re being validated, not interrogated.

Same scientist, same questions, different context: detained in airport interrogation room on return journey. For most people, the adversarial framing switches gears. The “protect information” mode overrides “demonstrate expertise” mode. But not for everyone. Some researchers cannot turn off the “defend my science” reflex even in clearly adversarial contexts. The professional conditioning runs too deep.

The distinction isn’t about the questions. It’s about the frame.

Recognition of the inverse application didn’t come from being particularly clever. It came from having a specific unmet need. I was working as a federal scientist at DHS, but once you look through the lens, the lens has already looked back at you. Years earlier I’d paid my way through college in part with rock climbing sports photography and videography. I wasn’t making money with photography anymore, but I still saw the world through the lens and through the microphone. That way of perceiving persists.

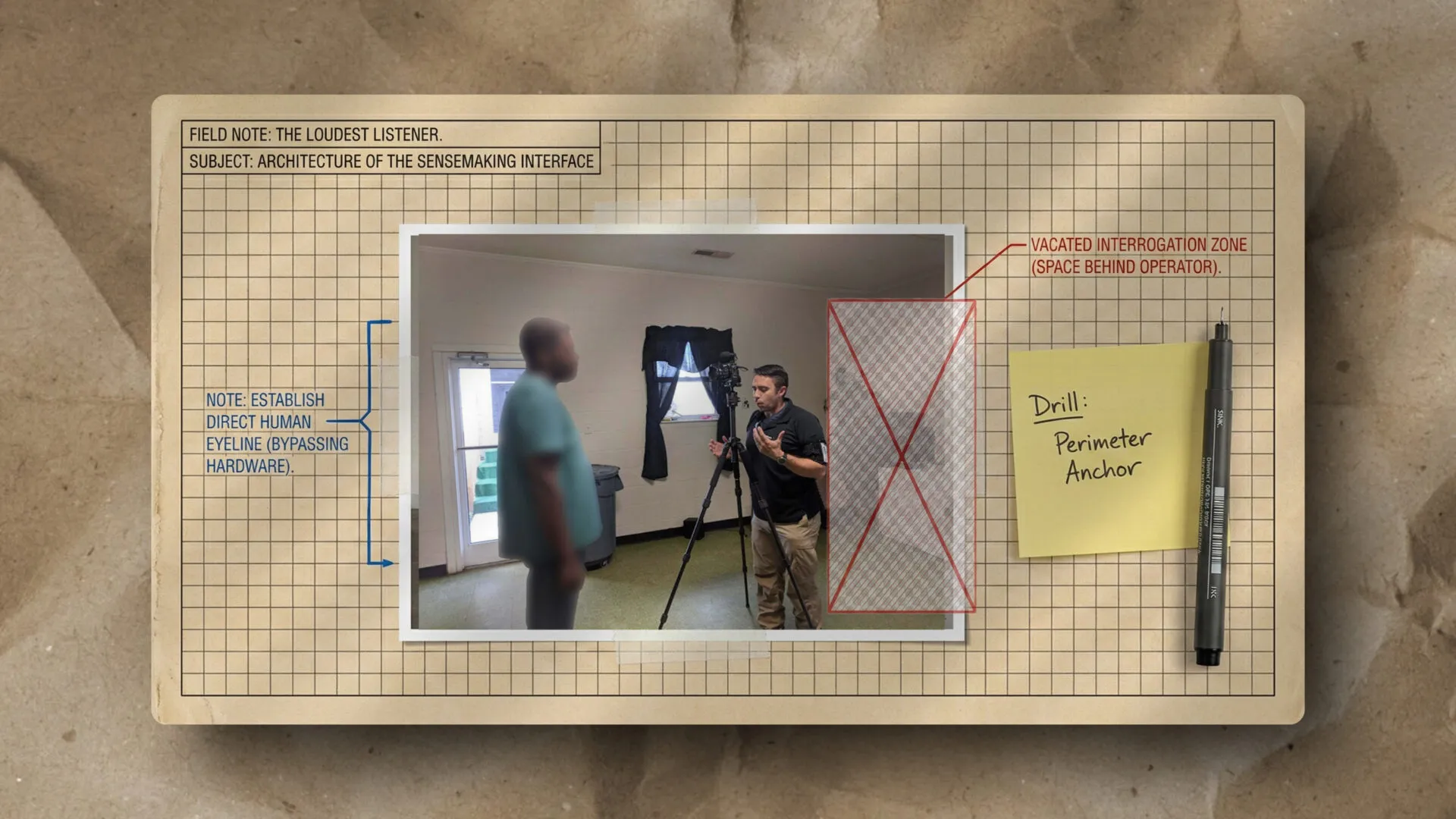

None of the photo or video training I’d taken even scratched the surface of the actual problem. That training focused on craft services (making sure someone has a bottle of water), technical camera work, lighting, editing. Nothing about creating the interpersonal conditions where non-actors would naturally drop into expert mode and provide detailed, authentic responses.

The anti-elicitation training clicked because it addressed precisely the gap in the filmmaker’s toolkit. The techniques being taught for adversarial extraction could be inverted to solve the actual problem: getting government practitioners comfortable enough on camera to demonstrate their expertise rather than perform explanations of it. The technical requirements of the filmmaker (authenticity) and the technician (elicitation) shared an identical structural need. This was like unboxing a new tool you purchased for one job and discovering that it fit an existing (but unmet) need.

Fast forward through years of government video interviews. Subjects aren’t trained actors. They’re practitioners who get self-conscious when cameras appear. Standard interview framing (“tell me about your role”) triggers explanation mode (abstract, stilted). The inverted technique creates the collegial expert-validation context. Not extracting information they want to protect, but helping them access information they want to share.

The activation mechanism: “someone is genuinely interested in my work and wants to understand the details.” This drops them into expert mode where providing thorough answers feels natural and rewarding rather than exposing or performative.

The Ethics of the Inversion: Stewardship vs. Exploitation

A common question arises: if these techniques are derived from adversarial elicitation, is the process manipulative? The distinction lies in Informed Consent and Stewardship. > The adversary is performing a Heist (extracting information to harm the subject and destroy their context). The elicitor is performing an Audit (accessing expertise to preserve the subject’s value and strengthen the mission). It is the difference between Exploitation and Optimization. The goal of guided sensemaking is to empower the expert to share what they already want to share, but cannot access due to the expert blind spot.

–> This: (An important boundary: this doesn’t work if someone feels like they’re in a deposition. To be clear, the vast majority of technical government officials have received zero media training. They’re often thrust into representing their organization by virtue of their title rather than their comfort level on camera. The “deposition mode” person is infrequent (not rare, but not common). It’s not that they’re literally preparing for an actual deposition, but they treat the interview as though it was one. If you’re working with someone like this, or if you’re an organization thinking of putting someone up for this kind of representation, please note: if they’re that uncomfortable, please don’t do it to them. You’re distorting the signal and causing damage to both the person and the knowledge you’re trying to capture.)

The Pivot: When the Lens Looks Back

It is easy to look at that scientist and think, “How could they miss that change in context?” But the professional schema is a powerful drug, and the expert blind spot is not something other people have. I know this not because I observed it in others, but because I fell into the exact same trap myself years later, when the mission pressure was on me.

Break

Years later, during US Army Corps civil-military emergency preparedness training in Moldova and Ukraine. The Iceland ash cloud erupts. Our plane diverts from Moldova to Austria (entirely wrong direction from Ukraine destination). I briefly consider land travel, then realize the route crosses Transnistria. State Department explicitly prohibits this.

But there was a competing force in my head. Because of the ash cloud timing, I was the only US representative on the continent. The professional programming kicked in: I need to get to Ukraine because I need to present “our technology,” “our science.” The mission obligation schema was pulling hard against the risk assessment. The “Terror of Uselessness” was beginning to creep in and impact judgement. I was the only US representative physically present and the professional programming was demanding that I present the science, regardless of the terrain.

(Note: For the technical breakdown of how this specific fear disrupts orientation, see the Doctrine 11 Companion: Agency vs Outcomes aka The Terror of Uselessness).

This was the first visceral realization: I didn’t want to be on the receiving end of what I’d been trained to recognize and counter. Getting detained on a US official passport in that region could expose me to significantly more than elicitation techniques. The lesson wasn’t about resisting interrogation; it was about recognition and avoidance. Sometimes the best countermeasure is simply not being there in the first place.

This is the same reflex as the scientist who can’t turn off “defend my science” mode even in the interrogation room. Professional conditioning trying to override judgment about context and consequence.

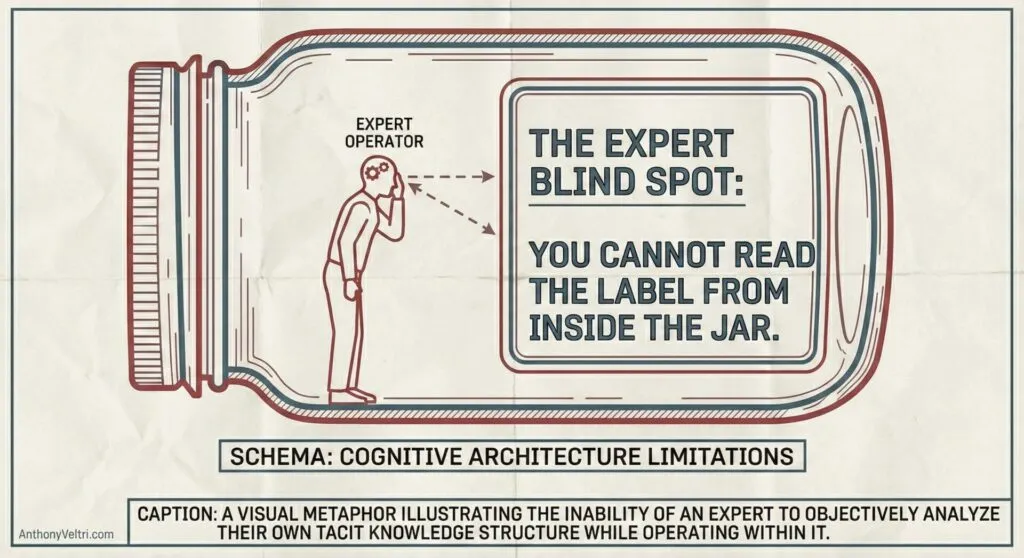

The broader recognition came later: I’d been performing a specific methodology on others for years (accessing their expert schema, then systematically converting operational fluency into teachable frameworks) but couldn’t perform it on myself. The expert blind spot. You can’t examine your own cognitive architecture using that same architecture.

Schema

What was documented in the Government Video Guide:

Phase 1 (On-camera safety work):

- Reduce threat perception

- Remove performance pressure

- Get them into expert mode (operational demonstration rather than abstract explanation)

- Keep them in that mode

What wasn’t documented in the Guide (the bigger unlock):

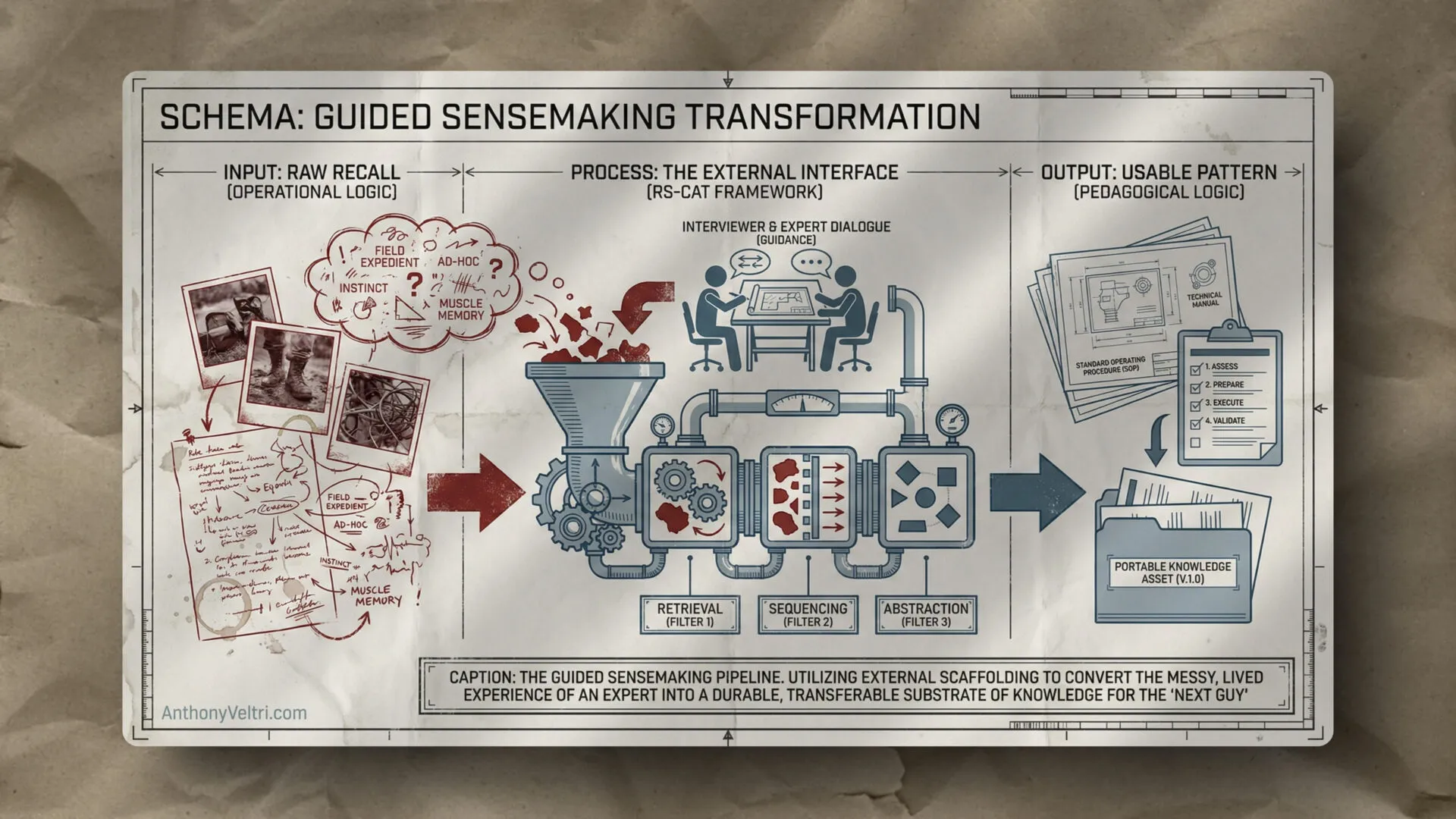

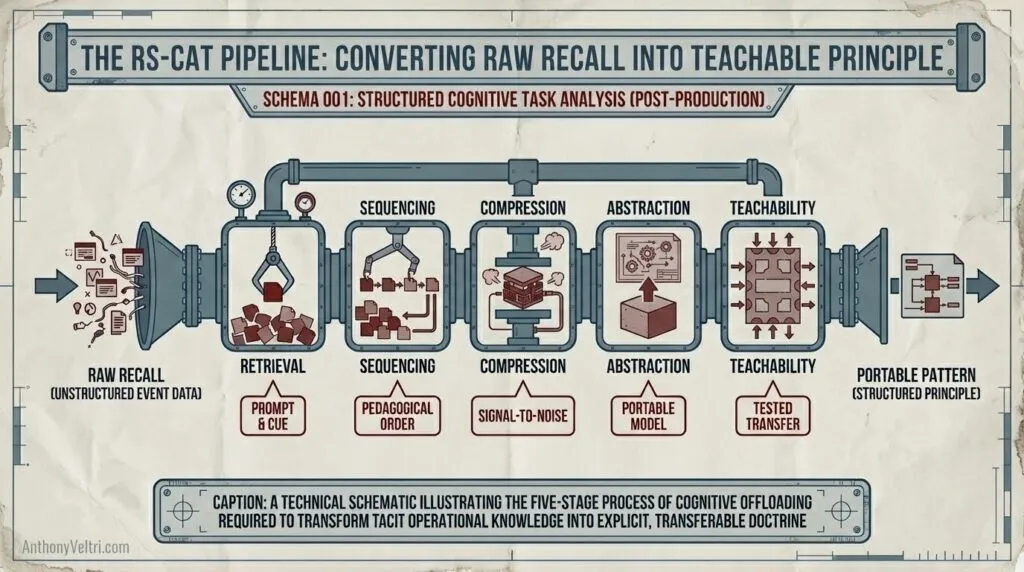

Phase 2 (Post-production cognition work): The RS-CAT pipeline that converts raw recall into teachable principle.

RS-CAT: Retrieval, Sequencing, Compression, Abstraction, Teachability

Raw Input ->

Retrieval: Pull the memory forward with prompts, cues, and constraints. Not everything the subject knows, but the pieces that matter for the specific teaching objective. Understanding the difference between operational detail (what they needed at the time) and transferable principle (what learners need to absorb the pattern).

Sequencing: Order information to match how humans learn, not how experts experienced it in real-time. The pattern: setup, friction, choice, consequence, takeaway. This isn’t chronological sequencing, it’s pedagogical sequencing.

Compression: Reduce signal-to-noise ratio. Experts include context they needed at the time but learners don’t need to absorb the pattern. Find minimum viable detail that preserves authenticity while enabling transfer. This is cognitive offloading (feature, not failure).

Abstraction: Extract the underlying rule without losing the texture that makes it believable and applicable. Too abstract becomes consultant-speak. Too concrete stays anecdote. The balance point: portable model grounded in real consequence.

Teachability: Convert “my story” into “a pattern someone else can apply in their context.” Identify which variables can change (domain, scale, resources) while the core pattern holds.

–> Useable Patterns

Why RS-CAT doesn’t work on your own expertise:

- Self-retrieval pulls everything (you don’t recognize what matters to others)

- Self-sequencing follows operational logic (not learning logic)

- Compression fails because you know why every detail mattered

- Abstraction either loses texture or stays in anecdote

- Teachability can’t be tested because you already know it

This is why we care about the ‘Next Guy’ (even when that guy is our future self): you need a different cognitive architecture to audit the system than the one you used to build it.

Why reviewing old video footage doesn’t produce the same clarity:

I used to think that I could just re-watch my old footage to review and process at a later date. (Granted, re-watching is better than storing the hard drives away in a drawer and not looking at the videos at all for 10+ years) What I found was (for me) watching yourself only preserves the Event. It does not provide the Distance required for Abstraction. You are still trapped in the “Operational Logic” of what you felt at the time. Old footage preserves events, but doesn’t reliably produce:

- Clean sequence (what mattered first, second, third from learning perspective)

- Compression (signal without noise)

- Abstraction (what’s reusable versus what’s just context)

- A principle someone else can apply tomorrow

Writing, outlining, and re-sequencing aren’t “note-taking.” They’re external representations that change what your brain can see and manipulate.

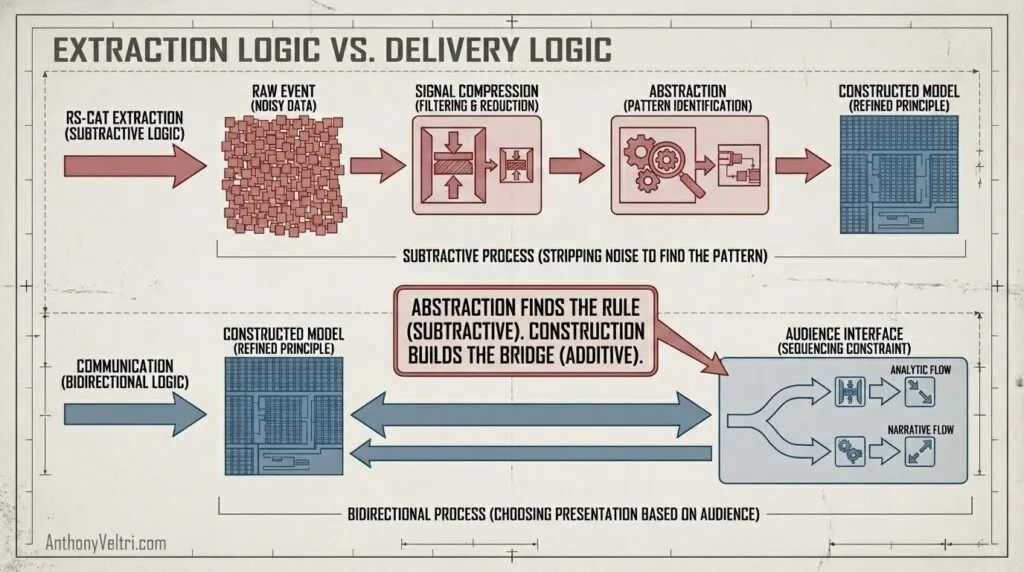

Question: “Why does watching old footage fail to provide useful distance?” Answer: Because footage preserves the Event, not the Abstraction. When you watch yourself, your brain re-activates the “Operational Logic” (what you felt). You need the “Pedagogical Logic” (what it means), which (for me) requires external scaffolding to see the structure.

External elicitation provides cognitive distance:

The elicitor doesn’t have the subject’s expertise, so they naturally:

- Ask sequencing questions that force pedagogical rather than operational ordering

- Flag when compression loses essential context

- Test abstraction by trying to apply it to different domains

- Verify teachability by demonstrating understanding

The elicitor is the Steward of the Learning Logic, while the expert is the Steward of the Operational Logic. The expert is too busy “doing” to see “how” they are doing it. The elicitor’s “ignorance” of the domain is what forces the expert to build the bridge.

The same methodology applied to Hurricane Katrina responders, Forest Service analysts, and coalition partnership teams. RS-CAT was being performed on their expertise to create teachable frameworks. But it couldn’t be performed on my own expertise without external scaffolding.

Connection to anti-elicitation inversion:

Anti-elicitation training teaches adversary techniques:

- Building rapport to lower defenses

- Asking questions that trigger expert schema

- Sequencing questions to construct complete picture

- Making subject feel validated to continue talking

The inversion for willing subjects:

- Building rapport to access authentic expertise (not performance mode)

- Asking questions that bypass self-consciousness

- Sequencing questions to reveal decision logic they use but don’t articulate

- Making subject feel understood so they stay in operational mode

The RS-CAT framework extends this from accessing expertise to making it transferable.

What happens with external elicitation (like this conversation):

Using external cognitive scaffolding to perform RS-CAT on expertise when the expert blind spot prevents self-examination. (thinking partner, AI Summary, etc) The subject maintains pattern recognition, decision-making, systems thinking. The elicitor provides the distance needed to see structure that can’t be seen from inside.

Authorization Assessment: Cover for Action, Cover for Location

A Common Cognitive Challenge (and why the framework is counterintuitive):

When someone has legitimate credentials, authorized presence, and appropriate-seeming activity, the natural human response is: “This person is trustworthy.” Conference badge + asking technical questions = legitimate colleague. Building access + uniform = authorized maintenance. Valid ID + plausible story = safe interaction.

This shortcut exists because constantly verifying everything would be cognitively exhausting. But it’s exactly the vulnerability that adversarial actors exploit.

(During development of this section, a reviewer encountered this exact challenge. When first hearing “cover for action and location,” the reviewer pattern-matched on “defensive security framework” and inferred the logic would be: “person WITH cover = probably legitimate, person WITHOUT cover = might be eliciting.” The immediate correction: the actual teaching is that someone WITH cover can STILL be eliciting you. That’s the entire point. The most effective elicitation happens when the adversary has complete legitimacy.)

This connects directly to Zero Trust principles (see Doctrine 21): “Never trust, always verify” – even when credentials appear valid, presence appears authorized, and activity appears appropriate. The presence of cover doesn’t eliminate the need for verification; it just changes what needs to be verified.

The anti-elicitation framework:

Cover for Location means someone has plausible reason to be in that physical space.

Cover for Action means someone has plausible reason to be doing what they’re doing in that space.

At a scientific conference, every attendee has both types of cover. They’re supposed to be there (conference badge, registered participant) and they’re supposed to be asking technical questions about your research (that’s what conferences are for). This is what makes elicitation so effective in that context. The adversary isn’t waiting for you in the supermarket parking lot asking suspicious questions. They’re sitting in the session asking the same questions a legitimate colleague would ask.

The training emphasized: having cover does not mean you’re safe. The most dangerous elicitation happens when the adversary has complete legitimacy. Don’t relax your guard just because someone “should be here doing this.”

The cognitive inversion for authorization decisions: If someone has cover for location and action, any additional restriction they claim requires explicit policy justification. If they can’t articulate the policy, it’s procedural theater.

Light switch example (Congressional video, USDA):

Filming after hours for an infrastructure report to Congress. We had authorization for building access (cover for location) and authorization for filming (cover for action). These were important buildings – the kind where people are genuinely careful about protocols.

Facilities maintenance had been briefed about our presence in their weekly report. That morning, they met us at the building, let us in, and told us “you should be okay, but come find us if you need anything.”

In one room later that day, my colleague wanted to call facilities maintenance to turn on the lights. Regular wall switch, not specialized controls.

Initial pattern match: “He works here, I don’t. He probably knows building protocols I’m not aware of. Defer to local knowledge.”

But I had my own technical knowledge. High-intensity discharge lights (sodium vapor, metal halide) can be damaged by rapid on/off cycling – that’s why they’re typically controlled by keys or special tools rather than standard wall switches. These were standard office fluorescent or accent lighting. And we weren’t cycling them rapidly – single use: on, do the work, off.

So I asked questions: What’s the specific concern? Is there something about these lights I should know? What procedure requires calling maintenance?

His answer: “We need to be respectful of their space.”

This wasn’t malicious or obstructionist. He was being appropriately cautious in an important building. And there was a legitimate consideration: this particular room’s lights would be visible from other areas of the building and from outside. After-hours lighting in what should be a closed building could reasonably trigger security concerns or questions.

But facilities had been briefed about our presence in their weekly report and met us that morning with “you should be okay, but come find us if you need anything.” Security had also received a brief at the beginning of the week noting our presence. If building security or anyone else noticed the lights and investigated, we could show authorization. The people who would notice the lights were the same people who’d already been briefed we’d be there.

Tracking down facilities to flip the switch wouldn’t change the visibility concern – we’d still have lights on in a building after hours, we’d just have wasted their time getting permission for something they’d already authorized.

The real question wasn’t “will anyone notice the lights?” but “do we have authorization that covers being noticed?” The answer was yes.

Test applied:

- Cover for location? Yes (authorized building access, facilities briefed and provided access)

- Cover for action? Yes (authorized filming, facilities aware of our presence)

- Specific technical concern? No (standard lighting, single use)

- Articulated policy basis for restriction? No (personal preference to defer, not institutional requirement)

- Prior authorization from facilities? Yes (“you should be okay, come find us if you need anything”)

- Downside risk? Zero versus wasting everyone’s time

Result: Turned on lights, completed filming, mission succeeded.

Transnistria example (US Army Corps civil-military training, Moldova/Ukraine):

Iceland ash cloud diverts our flight to Austria, entirely wrong direction from Ukraine destination. I’m the only US representative on the continent. Mission pressure to deliver technical findings in person. Land route from Austria requires crossing Transnistria (contested territory, frozen conflict zone, Russian military presence).

Initial pattern match: “This is just another bureaucratic obstacle slowing down the mission. I operate at edges. Route around it. Find a way.”

Then anti-elicitation training kicked in: State Department has explicit hard line against official travel through Transnistria. Not invented deference. Not risk-averse bureaucracy being cautious. Actual institutional policy with actual consequence likely to be enforced by a border guard (not a slap on the wrist from my own command).

Test applied:

- Cover for location? Yes (official US representative on mission)

- Cover for action? Yes (authorized to deliver technical findings)

- Articulated policy basis for restriction? Yes (State Department prohibition, no institutional backup if detained)

Recognition: My expert schema was trying to code high-consequence scenario as routine obstacle because the surface pattern (bureaucratic restriction during mission tempo) looked familiar. This was classic Recognition-Primed Decision Making (RPDM) failure – mistaking a low-frequency, high-consequence event (contested border crossing with no institutional backup) for a low-frequency, low-consequence event (typical bureaucratic friction that’s annoying but harmless). Both are “unusual situations,” but the consequence profile is completely different.

Result: Waited for ash cloud to clear, took conventional flight route, arrived in Ukraine several days ahead of full US contingent anyway.

The discriminator:

Both scenarios involved mission pressure and administrative restrictions. The difference wasn’t about how important the mission felt or how inconvenient the restriction was. The difference was policy reality.

Light switch: Cover present + invented procedure = theater. Challenge it.

Transnistria: Cover present + real policy = legitimate boundary. Respect it.

The trap: Expert schema optimized for “make the mission happen” can mis-code legitimate boundaries as bureaucratic theater when surface patterns match familiar obstacles. Having authorization for location and action creates permission to challenge restrictions, but doesn’t override actual policy when it exists.

Question: “How do you distinguish real policy from procedural theater in the moment?”

Answer: Ask for the specific policy. Not “we should” or “it’s respectful” or “that’s how we do it.” What is the actual rule, where is it documented, and what are the consequences for violation? Theater cannot answer these questions. Real policy can.

This is the same framework inverted: anti-elicitation teaches “cover doesn’t guarantee safety, stay vigilant.” Authorization assessment teaches “cover shifts burden of proof to the restriction, but real policy still governs.”

Quick Diagnostic”

| Signal | Light Switch (Theater) | Transnistria (Policy) |

| Cover for Location | Yes (Authorized Access) | Yes (Official Mission) |

| Cover for Action | Yes (Authorized Filming) | Yes (Technical Delivery) |

| Restriction Basis | “Respect/Preference” | State Dept. Prohibition |

| Verification Result | Procedural Theater | Legitimate Boundary |

| Action Taken | Challenge & Execute | Respect & Route Around |

The Haptic Boundary: When the Novice Hits a Wall

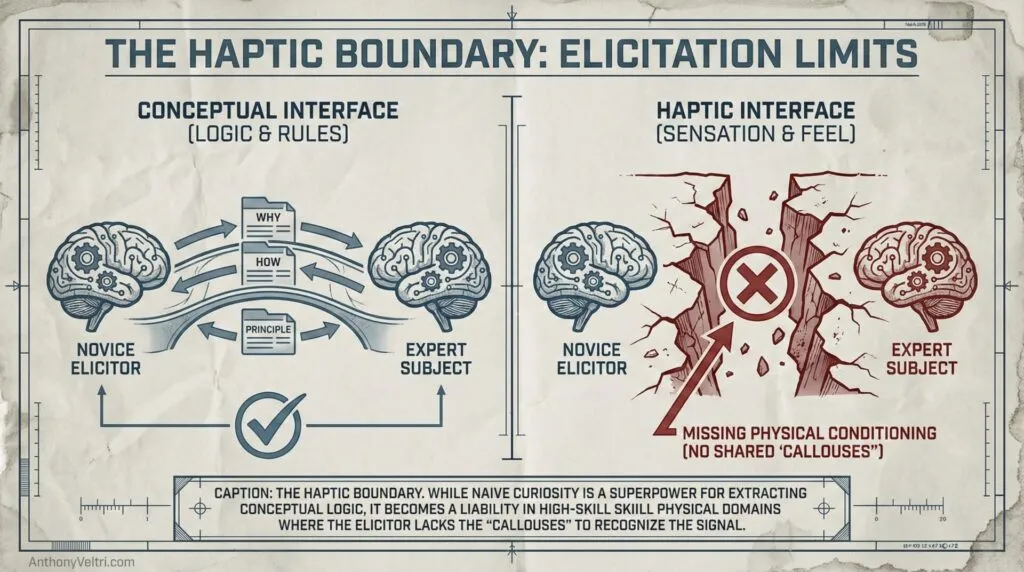

A common objection is that the elicitor must be a subject matter expert (SME) to be effective. This is often true in the “Garden” of academic theory, but in the field, it is frequently (but not always) the opposite of the truth.

The “not always” is a critical boundary. Naive curiosity is a legitimate superpower when you are extracting Conceptual Logic (science, cognitive ideas, or procedural rules). However, this logic breaks down when you enter the realm of Haptic Expertise. If the objective is to elicit information on high-end violin technique or the specific mechanics of a Jiu-Jitsu transition, a total novice is a liability. You aren’t looking for their “experience” of playing or what it “means” to them. You are “looking” for the Feel.

Until you have developed a specific level of skill, you cannot actually “feel” the move. If the elicitor hasn’t felt that specific tension or balance point themselves, they have no baseline to recognize the signal. They are deaf to the “feeling” because they lack the physical conditioning to host the memory. In these high-skill domains, the elicitor must have enough “callouses on their hands” to hold a conversation in the language of sensation.

The Novice Advantage vs. The Status Checker

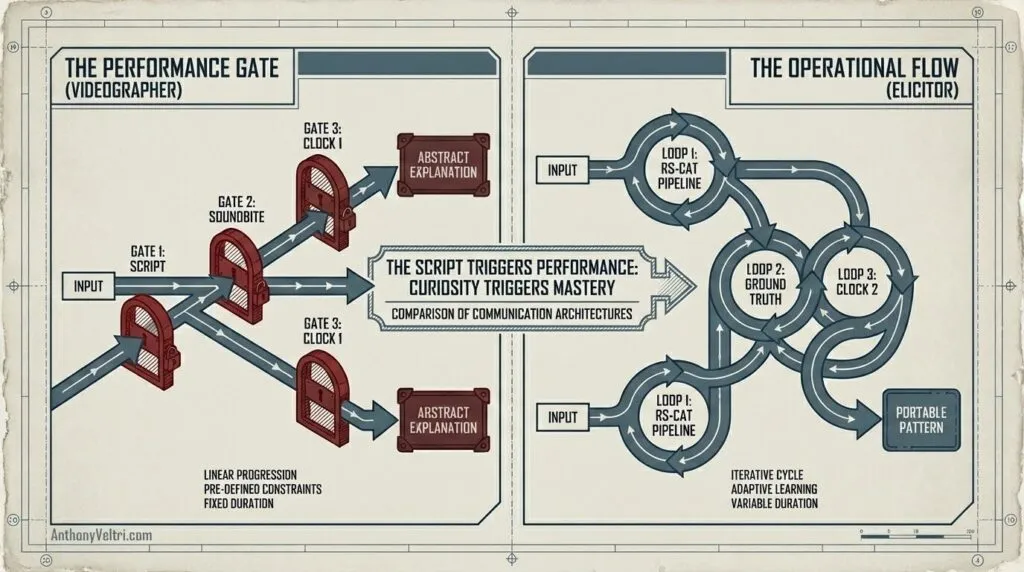

Outside of that haptic boundary, a novice elicitor will still outperform a high-end videographer. The videographer is optimized for the Pixels (Clock 1: Hype and Performance). They are looking for the “Perfect Shot.” Their scripted questions (e.g., “Tell me about your role”) act as a Performance Gate. This triggers the expert’s explanation mode: abstract, stilted, and socially safe.

In contrast, the elicitor (even a novice) is optimized for the Durable Substrate (Clock 2: Patterns and Logic).

The novice elicitor has a significant advantage in conceptual domains because they do not share the subject’s expert blind spot. This allows them to:

- Ask the “Stupid” Question: Forcing the expert to articulate the “Invisible” steps they usually skip.

- Focus on Flow: Tracking the decision logic rather than checking off a list of approved talking points.

- Trigger the Expert Schema: By showing genuine, naive curiosity, they move the subject from “Performing for a Camera” to “Helping a Peer understand the mission.”

The videographer is a Status-Checker (did you say the right words?). The elicitor is a System-Checker (does the logic hold?). You do not need a domain expert to find the Dragon. You just need someone who knows how to hold the focal plane.

Question: “Is the Elicitor just an interviewer with a fancy name?”

Answer: No. An interviewer looks for a “Soundbite” (Clock 1). An elicitor looks for the Decision Logic (Clock 2). The videographer checks for Pixels; the elicitor checks for the System.

Simple self-protocol (when external elicitation isn’t available):

30 minutes, one memory, one output

Inputs:

- One short clip or recalled incident

- One question: “What would I want a smart peer to copy from this?”

Steps:

- Two-minute voice dump (no editing)

- Write the five-sentence spine:

- Context

- Problem

- Move

- Result

- Principle

- Extract the pattern in one line: “When X, do Y, because Z”

- Build micro-checklist (3-7 bullets)

- Add one boundary: “This does not apply when…”

Last Updated on December 27, 2025